State-mandated antler restrictions. The idea pitted friends against friends … brothers against brothers. It was not a pretty situation, and it ruined deer hunting for a lot of families. However, did it achieve what it was meant to do? Today, 20 years later, we take an in-depth look at the most radical whitetail hunting change to sweep across an entire state in most of our lifetimes.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of Deer & Deer Hunting Magazine. It has recently been honored as the Best Magazine Article of 2022 from the Pennsylvania Outdoor Writers Association; and honored with the Lantz Hoffman White-tailed Deer Award from the Professional Outdoor Writers Association, and also the Outstanding Achievement in the Pinnacle Awards competition of POMA.

You are reading: The Pennsylvania Deer Controversy, 20 Years Later | Deer & Deer Hunting

by Steve Sorensen

It was serious enough to call “the deer wars.” In 2002 Pennsylvania, arguably the most traditional deer hunting state in the union, began protecting as many yearling bucks as possible. To make a buck a legal target, his antlers would need 3 points on one side in the mountainous regions of the state and 4 points in most other areas. Higher antlerless quotas were also implemented to reduce the population of whitetails to a level where the habitat could recover from decades of overbrowsing.

It was a major skirmish in the deer wars, but it wasn’t fought against deer. It was fought against decades of policy that caused the overharvest of bucks and the underharvest of does. Some traditional hunters viewed it differently. They saw it as a war against a way of life where almost a million hunters enlisted in “the orange army” and marched into the woods on opening day expecting to see lots of deer, and hoping one of them would be a buck they could tag and drag.

A New General

The new policies called “antler restrictions” (AR) and “herd reduction” (HR) were recommended by wildlife biologist Dr. Gary Alt, who had been appointed Deer Section Supervisor of the Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) in 1999. Dr. Alt was popular among hunters. From 1977 through the 1990s, he managed the state’s black bears and restored a thriving, healthy population of bears to the state. Could he change the direction of deer management too?

This wasn’t the first battle over deer in Pennsylvania. Some 50 years earlier, legendary Game Commission biologist Roger Latham advocated higher doe quotas to diminish the negative impact of deer on forest habitat. In an article in the February 1953 Pennsylvania Game News titled “Too Many, Too Long!” he wrote, “Most of our deer range is ruined… principally because too many deer have literally eaten it to death, even as they themselves are now starving.”

Many hunters disagreed, and the deer population continued to rise. In August, 1957 Latham (still advocating for a higher doe kill) was fired before the fall deer season began. Three years later, Latham wrote in a booklet for the National Wildlife Federation, “The science of wildlife management has come of age and barbershop biology is rapidly being replaced by true wildlife biology.” That was true, but it was still to play out in blood, sweat, and politics.

Deer would come to be known as a “keystone species,” a concept introduced by zoologist Robert T. Paine in 1969. A keystone species has a large effect on its environment and on the species that share its habitat. PGC biologist Glenn Bowers already understood that. After Latham’s firing he wrote, “There is little doubt that had more deer been harvested in earlier years, our forests would be more productive of deer food today, and also would provide better living conditions for small game species such as snowshoe hares, cottontails, and grouse.”

The Deer Wars

The deer wars began even earlier than the 1950s. Aldo Leopold, considered by many to be the father of modern wildlife conservation, faced the same issues in Wisconsin in the 1930s and ’40s. Wherever hunters focus on a high doe population as the key to future bucks, few seem to think much about the maturity of the bucks. Hunters accepted that Pennsylvania was a state where bucks had small antlers, but the truth was that bucks were killed off before they grew up. In some areas, 80% to 90% of the bucks were shot as yearlings wearing their first set of antlers.

In 1967, the year this writer killed his first buck, Pennsylvanian hunters reported a record harvest of 144,415 deer. By 2000 the calculated harvest exceeded 504,000. (In 1986 the PGC changed from reported harvests to calculated harvests.) The problem Latham saw had gotten worse.

Besides the failure to kill enough does, other factors also contributed to the problem. In the 1980s the invasive gypsy moth caterpillar caused an oak die-off across the state. Timber companies geared up to salvage the dead trees so they wouldn’t rot on the stump. Subsequent tree regeneration brought thicker cover, with plenty of browse for deer to eat and plenty to hide in. The decline in family farms created more cover, but without agricultural crops, a change that began as far back as the late 1890s and was an early driver of a growing deer population.

WATCH: THE DEER WARS ARE NOT OVER

Gary Alt’s Message

Alt understood that overcoming “barbershop biology” (to use Latham’s words) and getting the message out about “true wildlife biology” meant part of his job would be a public relations task. He began an exhausting tour on a scale that few old-time revivalists had the commitment or the energy for. Each winter during the 90 days preceding the spring meeting of the Board of Game Commissioners, Alt held 70 public meetings with hunters on their own turf at sportsman’s clubs and high schools across the state to win public support. Audiences averaged more than 500 people, sometimes well over 1,000. He aimed to be within 20 miles of every hunter who walked into the woods on opening day.

Alt held up in one hand the rack of a yearling four-point, and in the other hand a nice, three year old eight-point. He asked audiences which one they would like to shoot. He explained that for bucks to grow up, they needed better nourishment so they could exhibit their antler potential when they did reach maturity.

The tool that would allow more yearling bucks to survive their first season with antlers was antler restrictions. The tool that would achieve better forest health and better nourishment for deer was a reduction of the overall population by killing more does. Those twin aims would benefit all deer in multiple ways:

- Does: Fewer does would decrease food competition and allow the habitat to recover to produce more food than before. Does would more likely be bred during the first time they came into estrus and the rut would not spill over as much to a second or third month. They would have better nourishment during fawn development through the winter.

- Bucks: More of the breeding would be done by an older age class of bucks. With a more concentrated rut and fewer does to degrade the habitat, bucks would have better nutrition, recover from the rut more quickly, and would be in better health before the worst part of the winter arrived.

- Fawns: A more concentrated fall rut would produce a more concentrated spring fawn drop, so predators would have fewer opportunities to prey on newborn fawns, resulting in lower fawn predation. It would also mean fewer late-born fawns, so in their first winter fawns would be more mature and less dependent on their mothers.

Alt’s plan was bold, and despite its benefits came with a heavy cost. An outspoken contingent of hunters viewed Alt as public enemy number one. Despite death threats, Alt continued his tour wearing a Kevlar vest and accompanied by police escorts.

Pennsylvania’s success with antler restrictions is not a model for other states, but with its notoriously high yearling buck harvest, something needed to be done to shift the breeding responsibility from this vulnerable group and toward older bucks. Antler restrictions were chosen from a range of options, one of which was to shut down buck season for a year. In order to shift the breeding responsibility to older bucks, you need to have older bucks, and antler restrictions accomplished that.

Hunters dissatisfied with management policies often accuse wildlife scientists of being armchair biologists. The truth is that they want to be in the woods as much as possible because those are their favorite days. As a scientist, Gary Alt was never a creature of the laboratory, nor the cloistered office. His well-known experience crawling into bear dens puts him beyond such criticism. And his face-to-face meetings with hunters have no parallel among biologists. Nevertheless, his oversight of Pennsylvania’s deer management ended with his retirement in 2004 after a 27-year career with the PGC.

20 Years Later

Read More : Coyotes Kill Buck on Camera | Deer & Deer Hunting

Antler restrictions were not dreamed up out of thin air. In the mid-1990s and into the 2010s, wildlife researchers were finding that high pressure on young bucks to breed can stunt their growth or delay their maturity, and that breeding ecology is healthier when the herd has enough mature bucks to take the stress of breeding off young bucks. In other words, young bucks do better when older bucks are in the population.

Antler restrictions and herd reduction took the stress of breeding off young bucks and made a greater number of bucks age 2½ and older available for harvest. Many hunters believe deer hunting in Pennsylvania is now better than ever, and the evidence says the program was successful. In the 2021-22 season, 62% of antlered deer taken by hunters were 2½ years old or more; only 38% percent were 1½. In comparison to the years when 80% of harvested bucks were 1½ years old, that’s a dramatic improvement in buck maturity.

The first year of herd reduction (2002) resulted in an all-time record deer harvest of 517,529. Since then it has remained well above 300,000. In 2020-21 it rose to 435,180, higher than any season prior to 2000. In the 2021-22 season hunters harvested an estimated 376,810 deer, right in line with the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons. In the 2020-21 season Pennsylvania ranked second in antlerless harvests, third in buck harvests, and is second only to Texas in its number of deer hunters. In terms of the numbers, Pennsylvania hasn’t lost a step.

Although record books are not important to all hunters, more bucks are entering the state’s record book. (Pennsylvania’s book requires a minimum net score of 140″ for typical antlers on bucks killed with firearms.) Prior to AR, the decade following World War 2 was the decade with the most record book entries.

The AR policy is ongoing, but HR lasted only a few years. Dr. Christopher Rosenberry, Wildlife Management Program Chief for the PGC, said, “Beginning in 2006, we developed a deer management program that was guided by measurable objectives of deer health, forest health, and deer-human conflicts.” Habitat varies among Pennsylvania’s 22 Wildlife Management Units, so the PGC sets antlerless allocations based on these factors rather than on deer densities or a target population goal.

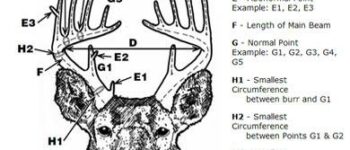

Is the Game Commission’s data the only data available? No. The Kinzua Quality Deer Cooperative (KQDC) is a consortium of private landowners, public land managers, scientists, hunters, and others interested in improving deer herd quality, forest ecosystem health, and the hunting experience in the big woods. The KQDC covers the Allegheny National Forest and surrounding properties consisting of 74,250 contiguous acres (114 square miles) mostly in McKean County. In 2000, two years before antler restrictions and herd reduction were put into place, the KQDC began collecting harvest data on deer ages, weights, antler points, and antler beam measurements showing not only that antlers are bigger, all age classes of bucks and does are heavier and healthier than before, and does are bearing larger fawns.

A few statistics from the substantial data gathered from deer brought to KQDC check stations from 2001 to 2021:

- Average field dressed weight of adult does increased from 96 pounds to 110 pounds.

- Average field dressed weight of adult bucks increased from 105 pounds to 137 pounds.

- Average antler beam diameter increased from 20mm to 31mm.

- Average antler spread increased from 10″ to 15.9″

John Dzemyan, a retired land manager with the PGC, compiles the KQDC Annual Report. He is a reservoir of information on deer habitat. He noted that “Deer numbers in 2005 were probably at the lowest any Pennsylvanian hunter had seen in over 70 years for the northcentral parts of the state. Slowly, the plants that make up good food supplies for deer started to recover.”

Dzemyan warns, however, that “in 2020, 2021 and 2022 deer numbers are up at levels that are not sustainable for deer or for deer food supplies.” With the rising deer population in the KQDC area, he cautions that overbrowsed habitat is a continuing concern.

Deer Hunters Have Changed

Alt’s efforts have changed the way hunters look at deer. One reason is obvious and it’s simply demographic. Hunters who were 55 to 75 years old in 2002 have mostly aged out of hunters’ ranks. Many were strong traditionalists.

On the other end of the age spectrum are hunters who were teenagers 20 years ago. Steve Sherk, Jr, now in his mid-30s, says, “Hunters my age didn’t have much exposure to the era when we killed lots of small bucks, and most are happy with what they kill now.”

Sherk has uniquely capitalized on the larger size and better health of big woods bucks. Ten years ago he began a public land guide service in the Allegheny National Forest. That would have been unthinkable 20 years ago. His dedication to scouting mature big woods deer has earned him a strong reputation, and his hunters kill some impressive bucks.

Of the many hunters between those opposite poles, most no longer view a high doe population as the key to killing their next buck.

No one should think, however, that major adjustments will never need to be made again. Habitat is always changing. Hunters are declining in numbers and political power. Non-hunters will gain influence. New wildlife research will broaden, complicate, and drive conservation issues. As long as deer hunters are passionate about deer and deer hunting, as long as humans have strong feelings and differences of opinion, the deer wars will not be over.

Where Gary Alt Is Today?

Gary Alt is retired in California but remains active. He responds to consulting opportunities and leads summer youth programs through the Wildlife Leadership Academy. His expertise is sought by states, conservation organizations, and at least one Native American tribe. One consulting job was in 2011 when Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker recruited him as one of three deer biologists to review, evaluate, and offer recommendations on Wisconsin’s white-tailed deer management.

The bigger question is about Alt’s own retrospective of his role in the deer wars. “Over the past 20 years I have been, and remain, very pleased with the results of our changes made back in 2002. Despite how difficult it was to implement, it was the right thing to do and I believe the rewards are likely to continue for many years to come.” he said. “After running the PGC bear research and management program for 22 years, I knew [the deer job] would probably end my career with the PGC, but I’d do it all over again.”

The average hunter’s eyes sometimes don’t see far beyond his home state, but 48 states and eight Canadian provinces have deer. They all employ biologists who keep up with current research and what’s going on in other states. Hundreds of people in universities across the country are involved in wildlife research. Several universities have leading national voices in whitetail deer management. Dozens of conservation organizations also hire trained biologists who advise their own state and local chapters, and consult with state agencies. Thousands of people are involved in deer management across the continent. Many are making important contributions in research, but few have impacted deer management at the everyday hunter’s level as Alt has.

Some of Alt’s Personal Reflections

Most people see the hard-nosed Gary Alt, the crusader, but that’s only one side of him. While many traditional hunters were his strongest opposition, he is a traditional hunter who loves firearms season and enjoys the camaraderie of family and friends. “I was never going to destroy deer hunting,” he said. “It’s too valuable to me. Some of my best family times have been created through deer hunting, and some of my best relationships were formed in camps and in the woods.” To this day he hunts deer in Pennsylvania not far from where he grew up.

Yet he recognized that “traditional” does not necessarily mean “good.” As a bear biologist, Alt was familiar with the problems the deer tradition caused. When a bad winter came, it was devastating to the deer herd. The winter of ’78 lasted a month longer than usual, and he started finding deer in bear dens. Mother bears would come out and drag a starved deer back to the den. When the fawn drop came, Alt found 77 dead fawns, and many of their mothers died also. He knew that the deer herd was in a precarious position. What he didn’t expect was that two decades later he would be asked to lead the deer program.

In his new position, Alt’s goal “was to break the back of a bad tradition.” That was part of his message at every public meeting, and after his lectures he asked a question: Would everyone who thought they could support his new policies raise their hands? “We usually had at least 80% of the people put a hand up.” Then he spent as much time as possible talking to individuals directly, hearing their stories and answering their questions.

Read More : How Whitetail Deer Respond and React to Hunting Pressure

He didn’t know how long it would take to trim the doe herd to an acceptable level, how long it would take to increase the average age of the bucks, or how long it would take the habitat to recover from decades of overbrowsing. Not long after the end of his tenure, the PGC shifted away from herd reduction to herd maintenance. Alt worried that he had not accomplished enough and that his goals would be reversed, but the habitat began to recover, the shift to herd maintenance came sooner than he anticipated, and the bucks got older.

Managing deer includes managing hunters, at least in terms of getting the hunters in the right place to kill deer. One part of Alt’s research was to look at how hunters hunted in firearms season. “We put 500 GPS devices on hunters to see how they cover the land. It was surprising that two thirds of the activity of the hunters was only a third of a mile from the road.” That wasn’t a new problem. Roger Latham noted the same tendency in his day. Getting hunters to go where the deer are is an ongoing challenge, one reason Pennsylvania instituted DMAP tags.

A couple of things happened Alt and his team didn’t expect. “We didn’t anticipate that it would be as successful as it was, as quickly as it happened. Another thing we didn’t see coming was the rapid growth of trail camera use. At the same time as we were implementing the program, hunters were putting more and more cameras into the woods. They started seeing much larger bucks than they were accustomed to seeing, and were more willing than we expected to pass up younger bucks, because they knew what they might see if they did.”

“Biologists rarely have an opportunity to make meaningful changes to management policy. I will always cherish the opportunities I had and am very happy with the results of my team’s efforts. When I’m in Pennsylvania or when I see what’s happening there, I know we made a difference. If I live to be 150, I will smile at the fact that we changed some things and made a dramatic difference. It was really hard, but the rewards were measurable and satisfying.”

Where Pennsylvania Stands Now

Prior to Dr. Alt’s tenure, Pennsylvania was not among the most respected states in deer management. That has turned around. In 2018 the PGC received the “Agency of the Year” award from the Quality Deer Management Association (now the National Deer Association). Biologist Kip Adams, Director of Conservation, noted the following in presenting the award:

- Pennsylvania is one of only five states in the U.S. to harvest more than 300,000 whitetails annually.

- In 2016, the most recent season for which data from all whitetail states was available, Pennsylvania hunters harvested over three antlered bucks per square mile, the second highest buck harvest rate in the nation that year.

- The 2016 season was the eighth year in a row that at least half of Pennsylvania’s antlered buck harvest was 2½ years old or older.

- Pennsylvania hunters also harvested more than four antlerless deer per square mile, the third highest antlerless harvest rate in the nation.

Are the Deer Wars Over?

As sure as World War 2 followed World War 1, more deer wars are ahead. Between 2011 and 2017, the PGC successfully fought several lawsuits brought by hunters. In the future, hunters must present a more united front because the foes of hunting are united. Deer management relies on scientific tools and policies based on the best research. But all of society is changing. Who’s to say the deer research of the future will continue to be led by scientists who value hunting? What’s to prevent people who deny the value of hunting from getting their university degrees and finding places of influence in wildlife management?

Whatever happens, several things are sure:

- Deer are a renewable resource — deer don’t stop making more deer. (That’s why state game agencies refer to a “harvest.”)

- We are nibbling away at deer habitat for shopping centers, housing, roads, airports, and other development, while deer are nibbling away at what the shrinking habitat produces.

- The number of hunters is declining, a demographic fact of life.

- Stresses between hunters, non-hunters and anti-hunters will continue, and maintaining healthy deer in balance with their habitat is a never-ending job.

It’s up to deer hunters to know what we’re talking about when fighting the deer wars, so neither deer nor deer hunters end up as casualties of the deer wars.

Were Antler Restrictions Designed to Make Pennsylvania a “Trophy State”?

One of the criticisms hunters made of the antler restriction and herd reduction program was that the Pennsylvania Game Commission wanted to convert Pennsylvania to a “trophy state” on par with Midwestern big buck states, and abandon faithful, traditional hunters in favor of luring out of state hunters.

That would be a foolish goal because no state favors non-resident hunters over its resident hunters. In some so-called “trophy states,” states, it’s difficult for a non-resident to get a whitetail tag. Resident hunters have always been and will continue to be the life-blood of Game Commission revenues, through both license fees and federal funding under the Pittman-Robertson Act.

Also, that viewpoint lacks understanding of the many barriers preventing Pennsylvania from becoming a big buck mecca. And although Pennsylvania has some pretty impressive antler genetics, deer management is more about nutrition than genetics.

- Better soil fertility grows bigger antlers, but Pennsylvania has lower soil fertility than Midwestern states like Ohio and Iowa. Lower soil fertility means lower deer nutrition.

- Climate has an effect too. Heavier snowfall and other weather factors in northern Pennsylvania lead to unpredictable mast crops. Nutrition is not only lower; it’s less reliable year to year.

- Pennsylvania lacks the sprawling farms of the Midwest where large tracts can be leased for guided hunts. As an older state, it’s properties have been broken up into smaller parcels.

- Pennsylvania has a longer firearms season and allows centerfire bottleneck cartridge rifles. Rifle hunting puts more pressure on deer.

- Pennsylvania has more hunters than all but one other state. With such heavy hunting pressure, few deer reach the 4½ to 6½ year old age class when their antlers exhibit their full trophy potential.

Interestingly, neither Ohio nor Iowa nor other so-called “trophy states” have any antler restriction program. Antler restrictions are not designed to create trophy bucks, and where older age classes of bucks already exist, the Pennsylvania approach to antler restrictions is not necessary.

— Steve Sorensen is a long-time contributor to Deer and Deer Hunting magazine and speaks frequently at sportsman’s dinners.

SOURCES

The Pennsylvania Game Commission 1895-1995: 100 Years of Wildlife Conservation, by Joe Kosack. Harrisburg, PA, 1995.

Deer Wars; Science, Tradition, and the Battle Over Managing Whitetails in Pennsylvania, by Bob Frye. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006.

A Tribute to Roger Latham by Ann Jenkins. Carlisle, PA, 2009.

Effects of Harvest, Culture, and Climate on Trends in Size of Horn-Like Structures in Trophy Ungulates, Wildlife Monograph, Monteith et al, 83:1-26; 2013.

Management and Biology of White-tailed Deer in Pennsylvania 2009-2018, Dr. Christopher S. Rosenberry, Supervisory Wildlife Biologist, PA Game Commission. Harrisburg, PA, 2009.

NDA’s Deer Report 2022, National Deer Association. Atlanta, Georgia, 2022.

Phone conversation with Gary Alt, April 25, 2022.

Source: https://raysthesteaks.com

Category: Hunting