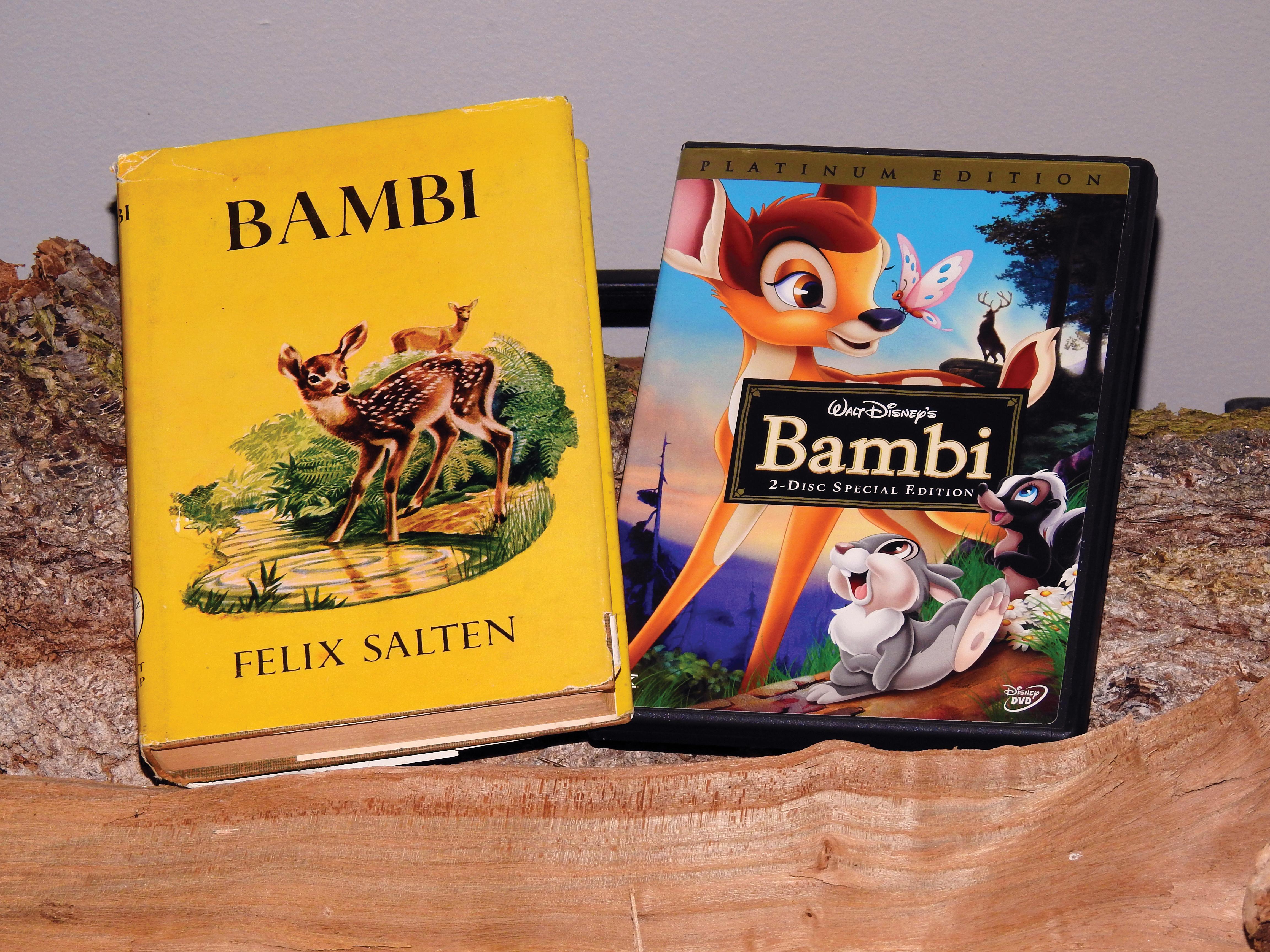

Maybe you imagine Bambi as a doe fawn, with big, friendly eyes, giant eyelashes, and beauty spots covering her adorable cartoon body. Maybe you’re familiar with Bambi’s little besties, a bunny named Thumper and a skunk called Flower. Maybe you thought Bambi was purely for children, a Disney creation that helped launch an entertainment empire of cartoon classics. Maybe you thought Bambi was a white-tailed deer. And maybe you thought the author was a wonderful writer of children’s stories.

Bambi — More Than Meets the Eye

All of that would be wrong — all except for the beauty spots. Bambi was a buck, not a doe. Bambi, the cutest caricature of all forest friends, did talk to other woodland citizenry but Thumper and Flower were not among them. Absent from the original 1923 novel, Disney invented the bunny and the skunk for its animated 1942 movie. In the book only deer have names, with one or two inexplicable exceptions.

You are reading: The Buck Fawn That Bamboozled America | Deer & Deer Hunting

Bambi was no Disney creation, and the book wasn’t written for children. It was originally written in German by an Austrian Jew whose books were banned and burned by the National Socialist Party of Germany. Yes, the Nazis hated it. They viewed it as sympathetic to Jews.

Bambi was not a whitetail. He represented the smaller roe deer species native to Europe. It was Disney that turned Bambi into a whitetail. Walt first conceived Bambi as a mule deer, but he had an animator from Maine who convinced him his audience would respond better to the more widely distributed white-tailed deer.

Even though the author was an intellectual who wrote for a sophisticated audience, Bambi won the hearts of children. Felix Salten was a theater critic, an editor, and a writer on everything from the arts to politics to literary criticism. He produced plays, wrote operatic texts and published novels (including an earthy “adult” fictional memoir). He rejected being labeled as a children’s author.

A Slow Start

Deer hunters might like to know some of these things, so let’s begin at the beginning. Bambi, a Life in the Woods, got off to a sluggish start. It first appeared in serialized form in an Austrian newspaper in 1922, then as a 1923 novel in Germany. When Adolph Hitler came along (also an Austrian) he viewed it as a pro-Jewish political allegory and a threat to the Nazi party. In 1936 Bambi was banned, but eight years earlier it had already been translated into English by Whittaker Chambers while he was still a Communist. (Hitler hated communism, believing it was a Jewish conspiracy.)

Nazi officials couldn’t control what was published in the English speaking world. Bambi was a big seller in America long before it hit the silver screen. The Book of the Month Club ordered a press run of 50,000 copies, and by 1942, 650,000 copies had been published.

In 1936 an MGM producer saw an opportunity for a film adaptation targeting a children’s audience, and bought the film rights from Salten for $1,000. He hoped to make a live-action film but quickly saw the difficulty in that, and passed the rights on to Walt Disney. Disney went to work on it in 1937 and it opened in theaters five years later as an animated production in the middle of World War II when Hitler was at the height of his power. The timing wasn’t good for Der Führer, although Americans wouldn’t have noticed any pro-Jewish message underneath.

Read More : 8 New Compound Bows for 2022 | Deer & Deer Hunting

American readers loved Bambi. Ambitious American marketing of the novel was just the beginning. The film was Disney’s sixth animated motion picture, the first with a storyline told only by animals, and a gold mine generating box office success.

Accolades for Bambi

In the foreword to the first English edition (the Whittaker Chambers translation), John Galsworthy went overboard with compliments. “For delicacy of perception and essential truth, I hardly know any story of animals that can stand beside this life study of a forest deer.” Galsworthy placed high value on the author’s feelings, “[Salten] feels nature deeply….” And on the reader’s, who “…feels the real sensation of the creatures who speak.” Never mind that fawns don’t speak, we know little of what they sense, and Bambi is hardly a “life study.”

Gratuitous praise flourished. Major magazines and newspapers heaped tribute after tribute on the novel, extolling the poetic nature of Salten’s work, its sympathy, its comprehension, its allegorical relation to life. A reviewer in the Dallas Morning News (October 30, 1938) praised Salten for giving animals human speech consistent with “their essential natures,” adding that “The reader is made to feel deeply and thrillingly the terror and anguish of the hunted, the deceit and cruelty of the savage.” The “savage” is, of course, the hunter. Perhaps that is why the author of the Foreword ended his brief page saying, “I particularly recommend it to sportsmen,” rather than to children.

Few seemed bothered by the deceit built into the story itself, but while most reviews gushed with acclaim, some were more balanced. A reviewer for Catholic World gave it general praise but also a criticism for Salten’s “transference of certain human ideals to the animal mind.” That’s a start, but now having been a cultural phenomenon for more than 90 years, its overall effect has not been positive toward hunters and the system that has made white-tailed deer thrive across North America.

The Bambi Effect on Hunters and Hunting

The success of Bambi can be seen in the fact that when many Americans see a deer today, they think of this fetching fictional fawn and its sweet innocence. How can anyone not love Bambi? By extension, only the “savage” would want to harm this lovable creature of the forest which surpasses man in virtue. And besides, animals are cute! And hunters? If there’s any Nazi analogy, there is it! We should be rid of Nazis, and hunters too!

To naturalists of the time (and to today’s wildlife biologists), the gushing sentiments are reminders of the earlier “nature faker” movement when nature writers habitually created life histories of animals that were audaciously anthropomorphic and shamelessly dishonest. Theodore Roosevelt firmly opposed nature fakers from the White House, yet the cultural effect of Bambi furthered that misleading practice. Despite its slanted message, Bambi, a Life in the Woods has been called the first environmental novel (Publishers Weekly, “A New Look for Bambi,” October 25, 1999). Never mind that it’s a distorted fictional story about talking animals. And never mind that concrete jungles across the land harm wildlife more than all the hunters in the nation ever could.

It’s time to say it — Bambi bamboozled America. Bambi became the most effective piece of anti-hunting propaganda America has ever seen. It depicts hunters as evil, not as wildlife management’s most important players and the best friends wildlife has. Because it became a children’s classic, it had far more success as anti-hunting indoctrination than it ever could have had as an anti-Nazi message. Its theater premier came at a vulnerable time for the American psyche. By the end of World War II when the hunting population increased and the economy boomed, viewers thought of every doe as Bambi’s mother. It’s no wonder hunters returning home from the war were reluctant to shoot does. None of this was Felix Salten’s fault.

Read More : Blood Trailing Tip 1: Use a compass.

Salten himself was an avid hunter himself, with a hunter’s understanding of the habitat where Bambi lived. He clearly framed the dependent relationship Bambi had with his mother as a hunter would know it. Hunting has deep roots in Austria, where a hunter often honors the deer with a traditional “last bite.” He picks some grass and puts it into the deer’s mouth. In Austrian society hunters value ethics and understand their vital role in nature. In Salten’s 1939 sequel, Bambi’s Children, he casts himself as an ethical and responsible hunter. He could not have dreamed that his allegory would become anti-hunting disinformation in a way that far exceeds any metaphorical parallels to Jewish life in the first half of the twentieth century. To this day, the Bambi syndrome infects the worldview of many people. And no wonder. The novel has been published in more than 30 languages and more than 100 editions.

The Bambi Syndrome

Thanks to Bambi, much of the non-hunting public sees the natural world as a blissful setting where Jupiter aligns with Mars, peace guides the planets and love steers the stars. They believe man is an intruder, he always spoil nature, and the natural world will take care of itself if only man leaves it alone.

They ignore the fact that man is an organic part in this system. They forget that as the world’s most consequential species man and his interests must be considered. A segment of the public even opposes scientific management of wildlife and habitat by game agencies, favoring cartoonish depictions of nature in order to sway more people to their sentimental view that animals will be better off if man has a hands-off attitude. All of this is ironic considering the “Bambi Syndrome” is a caricature which imposes human emotions and intellect on animals and even on the forces of nature. Never mind the incongruity. Just get the message — hunters are incurably bad.

Bambi is an excellent work — that’s undisputed — but much of its praise is misplaced. Deer hunters who read Bambi will be better informed about where a large part of the anti-hunting movement gets its steam, and will be better equipped to speak to those who have been buffaloed into thinking hunters are the bad guys.

— Steve Sorensen is an award-winning journalist and longtime D&DH contributor from Pennsylvania.

Read some of our other D+DH In-Depth articles:

D+DH In-Depth is our premium, comprehensive corner on America’s No. 1 game animal. In this graduate-level course, we’ll teach you about deer biology, behavior, and ultimately, how to become a better hunter. Want to be the first to get our premium content? Become a D+DH Insider for FREE!

Source: https://raysthesteaks.com

Category: Hunting