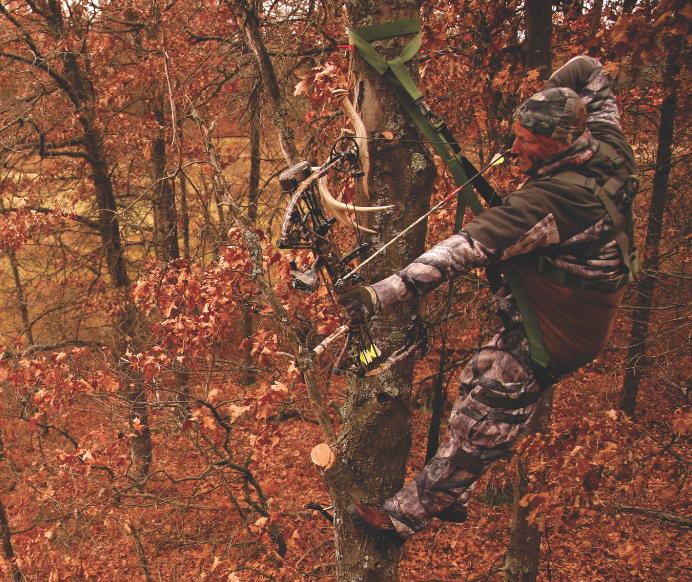

The buck drank deeply from the throat of the icy river, quenching his thirst caused by heavy rutting activity. For a moment, the deer had no inkling I was a mere 10 yards away, safely perched in an old ash 20 feet off the ground.

Without warning, the cursed wind ruined it all. A gust hit me head-on, loosing my rattling antlers from the hook where they were hanging and sending them clattering to the ground. If it weren’t so heart-wrenching it would’ve been funny — seeing the look on the buck’s face when a set of antlers landed inches from his face. In a mili-instant, the buck was gone.

The damn wind, I thought to myself. I could hear it whistling through the woods, and I swear it sounded a little like an old man laughing at my predicament. That’s it for me. I climbed down, headed home and called a friend to recount my terrible tale of woe.

“That’s why I never hunt in windy weather,” my friend said.

A lot of hunters agree with my friend. Not only do heavy winds make hunting conditions less predictable (and therefore less controllable), but there’s another reason many hunters stay inside on windy days.

“Besides, the deer just don’t move in high winds,” my buddy added.

This is a long-standing belief many hunters share. But is it true? Do deer stay put during windy weather, or is this just a myth that limits many hunters? I don’t know about you, but I don’t like basing a key part of my hunting strategy on only my personal experience and anecdotal evidence from other hunters.

So I decided to see what deer researchers have to say about the effects of wind speeds on whitetail movements. What I learned just might change what you thought you knew about the wind/whitetail movements relationship. Even if it doesn’t, it’ll make you a better-informed hunter. And as the saying goes, knowledge is power. So let’s get a better understanding of how wind speeds influence deer movements, and how to use this valuable intel to your advantage.

THE WIND/WHITETAIL’S RELATIONSHIP

Over the past 15 years, there’s been a lot of research conducted on whitetails to answer one central question: Why deer go where they go? For example, former graduate student Gabriel Karns examined which factors compelled adult bucks at Chesapeake Farms, Md., to temporarily leave their home ranges (where they spend 95 percent of their time) and go on excursions, defined as traveling outside of their home ranges for at least six hours.

Karns found that nearly two-thirds of the 20 bucks monitored with global positioning system (GPS) tracking collars made at least one excursion immediately before or during the rut, presumably looking for estrous does.

“We didn’t look at the effects of the wind on deer movements, although we could have, because our Chesapeake Farms site had its own weather station,” said Karns, now a post- doctoral researcher in the School of Environment and Natural Resources at Ohio State University. “One of the problems with studying how wind speed influences whitetail behavior is that publicly available weather data isn’t specific to your study site.”

Nonetheless, Karns believes that dead calm days and high winds (30 mph or more) bring deer movements to a screeching halt.

“I tend to see the best movement and activity in 5- to 15-mph conditions,” Karns said.

Only a few studies have looked at the effects of weather factors such as temperature, humidity and wind speed on deer movements. Professor Steve Demarais and wildlife manager Bob Zaiglin were the first to study the effects of wind speed on buck movements. In 1984, Demarais and Zaiglin captured and placed radio telemetry tracking collars on 25 mature bucks in South Texas to monitor their movements for four years. Using local weather information to monitor wind speeds, the researchers found that deer moved the most in light winds. Movements dramatically declined when wind speeds reached 15 to 19 mph, but then shot back up when wind speeds exceeded 20 mph. Demarais and Zaiglin concluded that it was best to hunt deer on calm and windy days.

“I think bucks moved more during calm conditions because they could hear well and therefore easily detect danger,” said Demarais, now a professor in the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture at Mississippi State University. “They may have moved more when winds exceeded 20 mph because they were responding more to noises, but it also could have been a function of the limited technology we had available at the time to determine the locations of deer.”

Radio telemetry equipment is limited in that it allows a researcher to only determine the location of each deer in the study several times a week.

In order to do so, the researcher must travel to the study site and use a large antenna to pick up the signal emitted by each deer’s collar. Although considerably more expensive, GPS technology enables researchers to capture the precise location of each deer at preset intervals (e.g., every 20 minutes) for months or even years.

Like Karns, James Tomberlin used GPS collars to track the movements of bucks at Chesapeake Farms. Tomberlin followed the movements of 18 adult bucks, recording their locations every hour for several months. Tomberlin looked at not only how breeding season impacted buck movements, but also climactic factors such as temperature, barometric pressure and wind speed. He found that the wind had little influence on buck travels.

“We found no consistent effects of wind speed on deer movements,” said Dr. Mark Conner, Tomberlin’s advisor and a researcher at Chesapeake Farms.

In 2010, Mississippi State University researcher Stephen Webb captured and fitted 15 male and 17 female deer with GPS tracking collars at the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation Wildlife Unit, a 2,999-acre parcel in southern Oklahoma. Like Tomberlin, Webb found no clear relationship between wind speed and whitetail movements for either sex during the study period, although only bucks were monitored during hunting season. Researchers didn’t see if does were affected by wind speed when hunters were afoot.

THE NEW STUDY

In 2015, Pennsylvania State University student Leah Giralico completed an independent study that compared hunters’ beliefs about how wind speed influences deer movements to data on deer movements collected in October 2013. Giralico surveyed more than 1,600 Pennsylvania deer hunters to see what effect, if any, they believed wind speed has on whitetail movements. Wind speed was differentiated using the following scale:

Light breeze — wind felt on the face and leaves rustle. Gentle breeze — leaves and small twigs constantly moving. Moderate breeze — dust and leaves lifted, small branches moving. Fresh breeze — small trees swaying. Strong breeze — larger tree branches moving, whistling in wires. Near gale — whole trees moving, resistance felt when walking into the wind.

More than half of all respondents believed that deer wouldn’t be affected until winds were strong, and nearly 90 percent indicated deer move less on windy days.

Next, Giralico compared survey responses to data collected by GPS collars on adult (21⁄2 years old and older) deer — 25 females and eight males — during October 2013. Before getting into what she found, it’s important to note that October wasn’t a very windy month. Wind speeds topped out at only 12 mph, so Giralico couldn’t see how heavy winds influenced deer movements. Wind speed was measured as calm (less than 1 mph), light air (1 to 3 mph), light breeze (4 to 6 mph), gentle breeze (7 to 10 mph) and moderate breeze (above 10 mph).

Surprisingly, all deer (both males and females) moved more during windy days, but less on windy nights. In contrast, calm winds seemed to make deer movements come to a screeching halt.

“Our data indicated that it takes just a little bit of wind to get deer to move,” said Dr. Duane Diefenbach, leader and adjunct professor of Wildlife Ecology for the Pennsylvania Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at Penn State University. “On calm days, it’s often warmer, so we aren’t really sure if deer didn’t move much when there was little wind because of the wind, or because of higher temperatures.”

Diefenbach points out another difficulty with interpreting data on the wind speed-deer movements relationship — it’s hard to parse out what effect, if any, other factors such as barometric pressure, precipitation and temperature have on deer movements. Statistical analyses and modeling will enable you to make only general statements about deer behavior. They will never explain why a particular buck chose to hunker down on a windy day, while another got on its feet and moved about.

Despite the limitations of the Penn State study, Diefenbach believes the results support the rationale of hunt- ing on windy days.

“The discomfort associated with hunting on windy days is probably affecting us more than it does deer,” Diefenbach added. “Rainy, windy weather probably isn’t affecting deer movements all that much.”

HIGH WIND HUNTING STRATEGIES As with any hunting strategy, safety should be the No. 1 priority. Don’t just disregard heavy winds — make them work to your advantage.

“Based on many years of personal experience, I believe that in many parts of the country, whitetails seek areas sheltered from high winds, especially during periods of intense cold,” said Brian Murphy, an avid deer hunter, wildlife biologist and CEO for the Quality Deer Management Association. “However, during the rut, bucks will still be on the move, so don’t overlook proven transition areas, even if they are exposed to the wind. In fact, the oldest buck I’ve ever taken with a bow was killed during the rut on the edge of a food plot during a 35 mph wind storm.”

If you have a non-bedding area that’s protected from the wind, hunt it on windy days. A low bottomland, the lee side of a ridge and just inside a conifer swamp are all great spots to sit during heavy winds. But just because you don’t have an area to hunt that’s sheltered from the wind, that’s no excuse to stay indoors. Not all deer are going to react to the wind the same way.

“I find that in states like Oklahoma and Kansas, where high winds are common, deer just aren’t affected by high winds,” said Dan Perez, bowhunter and co-owner of Whitetail Properties, a deer hunting property brokerage company. “In states like Illinois and Pennsylvania, windy weather will reduce deer movements, but less so during the rut. High winds will make deer move less for a day or two, but after that they get used to it.”

One strategy Perez uses is to get to field edges and fencerows earlier to intercept deer moving into agricultural fields to feed.

“Heavy winds really shake the trees and make a lot of noise, which spooks deer,” Perez said. “So I like to get out in more open areas away from the woods. Deer will move out of the woods earlier because they’re on pins and needles from all the noises they’re hearing.”

Perez is particularly vigilant about staying out of the woods on windy days when he’s targeting a particular buck.

“The last thing you want to do is have your scent move around in the woods and alert a deer that it’s being hunted,” he said.

Finally, carefully monitor the wind whenever you’re hunting, particularly on windy days. Pay attention to sudden shifts in wind direction, which can unknowingly carry your scent to unpredictable areas. Use a smartphone application that provides hour-by-hour wind forecasts to determine wind direction throughout your entire hunt.

Don’t ruin a hunting spot by sitting there if there’s even a chance the wind could carry your scent to deer. By making it your mission to fully understand how the wind behaves in different weather conditions at every stand location, you’ll make the wind work for you, regardless of how hard it’s blowing.

— Darren Warner is a passionate deer hunter, freelance writer and photographer. He lives in Michigan, and is obsessed with white-tailed deer.